A day in the life

Yesterday, we spent 12 hours filming in Vienna and meeting with Ukrainians and those helping them. It was a long, emotional day.

As someone who works fast, I adore other people who move as quickly as I do. It was less than a week ago when Teri Schulz called me and said she wanted to come to Vienna and spend a day with me. The resulting short feature will be in English on Deutsche Welle, and I will share a link when it is ready. I am so grateful to Teri that she had no issue with me writing about yesterday, because we heard so much, it was a lot to take in and at times extremely emotional, and I understand a lot of the material will not make it into the video story. Therefore, while my impressions are still fresh in my head, I would like to walk you all through our day.

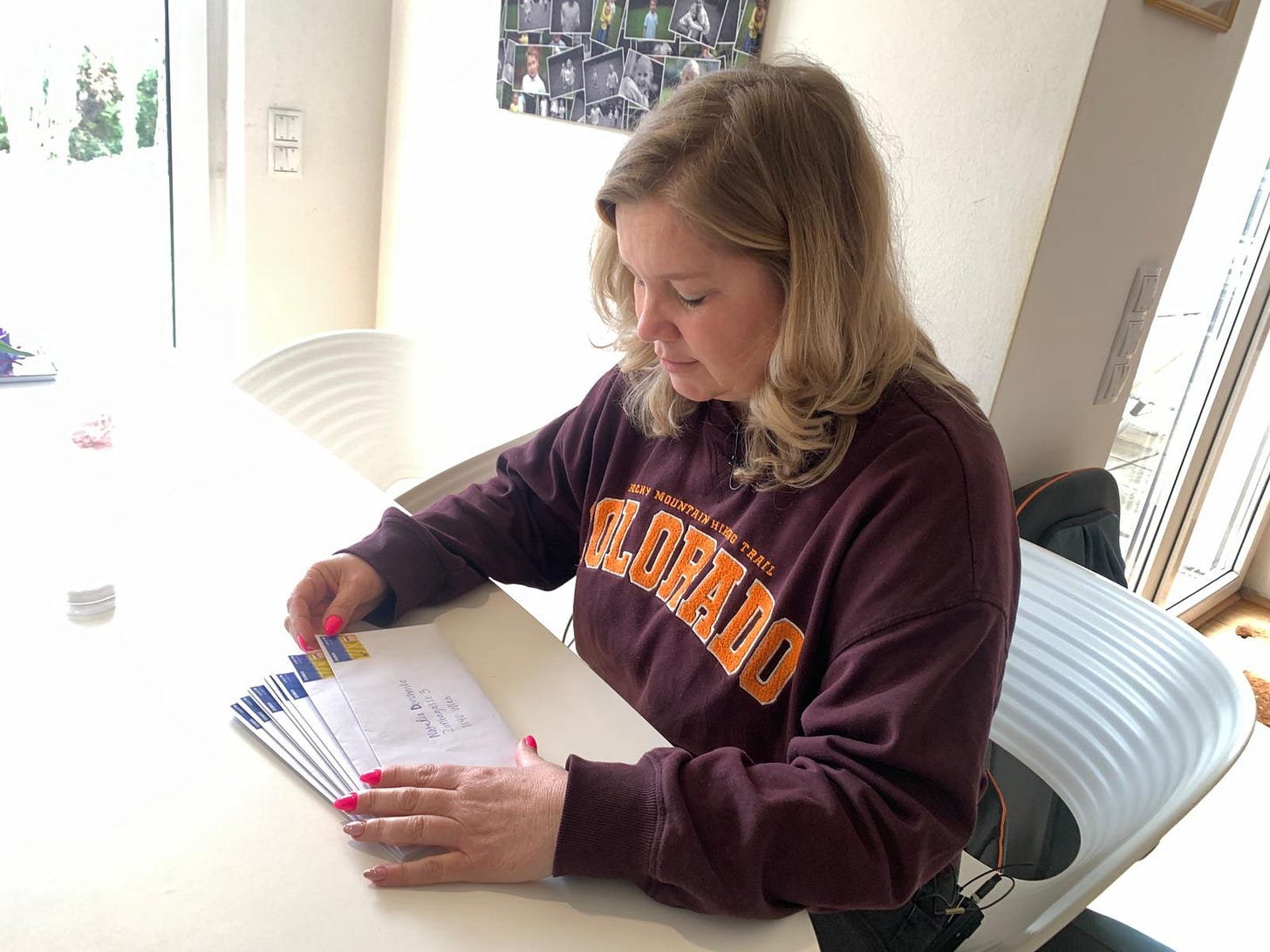

Teri and a wonderful local cameraman arrived at my apartment before 7am. They wanted a few scenes of me kissing the kids and husband goodbye as they left for school and work. The teenagers were not amused, but played along. Next, I showed them how I usually begin my morning: going through all my Telegram messages (and Messenger, and Instagram, and Twitter DMs), addressing and organizing my envelopes, checking how many cards I have to deliver that day, texting about in-person delivery appointments. Paperwork, much of which I do by hand. The joy of working alone is you can create your own system and don’t have to explain it to anyone. And I am super lucky, as I explained to Teri, that Mario takes care of our banking and admin and the bulk orders and distribution via Cards for Ukraine, which allows me to focus on corresponding with the Ukrainians who contact me directly and make in-person card deliveries to those refugees who just arrived to Austria and do not yet have a mailing address.

At 9am, we pulled up to the arrival center, and there was already a large group waiting for me. I had scheduled ten card “deliveries”, but there were more than nine people. Usually I try to meet in small groups of two or three, which makes it easier to have private conversations. I began to ask everyone their names, and then to explain how the cards work and where the nearest Hofer store is to them, and then to gently ask if anyone would be comfortable to speak with Teri on camera. There was a mom from Kyiv oblast with six kids. She didn’t want to talk publicly. Another older lady from Donbas who already received a card came again to try and whisper in my ear and ask if I have a job for her. I don’t, but I understand why she tries — she has no one else to ask. Teri spoke with a doctor from Ukraine who had come to bring her seventeen year old son, and then she will go back to Ukraine. As a doctor, she is in the reserves. She tearfully explained how it feels to bring your only child to Europe and leave him alone because your window of opportunity to do this closes with his 18th birthday. It was an emotional interview. Teri’s eyes watered up, as did mine, and I realized then with a heavy heart, the whole day was going to be like this.

Another lady came forward, Anna, originally from Severodonetsk, Luhansk oblast. She had been in Austria, in Salzburg, last spring, but had returned back to Ukraine when she heard her brother had been wounded and was in hospital. Once she returned to Luhansk (occupied territory), she then couldn’t get out for another six months. She finally managed recently to get out and come back to Austria, and is now waiting at the arrival center, hoping to be finally given a housing assignment. Her own apartment was destroyed in the early days of the war. Her late mother’s house is not far from Bakhmut and miraculously still standing. Her brother is doing better. She explains at the age of 66 she never thought in a million years she would have to start over with nothing in a foreign country. But she doesn’t complain or get teary. Everything is stated as a fact, and she expresses her gratitude to Austria and to me multiple times during the interview.

A third gentleman, Andrii from Kharkiv, is 63 years old and came alone to Austria just a few weeks ago because after staying in Kharkiv this entire time since the war began, he explained there is no work, there is no money, it is very hard to survive on one’s pension alone without the chance to earn a little bit extra, and he hopes to find work in Austria. He is a gardener. His wife stayed behind with her elderly mother. Andrii says he will go anywhere in Austria they send him. He then pulled me aside, and I tried to give practical advice: ask for work opportunities locally wherever you end up, as a private gardener you might be able to earn decent money if you ask the right people, or you could try the hotels, where they might give you housing on site. But realistically, I know it will be nearly impossible given his age and lack of language skills. He wrote me yesterday evening, as I was on the bus home, exhausted after a super long day, and asked when he can call me. I worry I gave him the false hope I can help him find a job. I will have to explain gently when he calls.

Next, we drove to a small park and playground in central Vienna where Teri interviewed Iryna, a mom of three from Kyiv who is struggling at the moment with the very difficult decision of whether to stay in Vienna or go home. She explains that the Austrian school may ask her son to repeat fifth grade for the third time, and the German test will be given again in May. She finds this all really damaging for his mental health and self-confidence, and wishes he could just do online school. Her younger children, twin girls, will be six in September and would be expected to start first grade then, but Iryna would like to keep them in kindergarten another year. She is proud that she did her duty as a mom and brought her children to safety — they do not know what it is like to take shelter from an air raid siren in the middle of their school days — but she also worries about their psychological well being being thrown into a system she has no choice to opt out of. Iryna explains what I have heard from so many Ukrainian moms: we do not plan to stay here longer than necessary, please let us make these educational choices for our kids, and do not apply to us the same rules the apply to locals and those who emigrated to Austria for good. Iryna also talked about how she and a small group of Ukrainian refugee women have been cooking home-cooked Ukrainian food for the little girls who were badly injured in the helicopter crash in Brovary and are being cared for in the AKH.

Our lunchtime stop (not that we had any time to eat) was Train of Hope’s new community center, a really wonderful space spread over several floors in an office building in Vienna’s 15th district, a short walk from a subway stop. As soon as we walked in, a Ukrainian woman looked up and greeted me. I had once given her a card, and I was embarrassed that I do not remember that encounter. Nina from Train of Hope gave Teri a great interview explaining many of the “challenges” Ukrainians face in Austria, in a wonderfully concise matter-of-fact manner. We then had a tour, and saw lunch in action. To my amazement, we also ran into Denis, who was with his wife and walking (!) using a walker. A huge improvement since last December, when he was wheelchair-bound. I met his lovely wife who is with him now, and said how happy I was to run into them and see he is doing better. Nina gave me a tour of the new space while Teri interviewed a young woman from Odesa who had only arrived in Austria recently, already had to move four times (!), and approached us and was eager to talk in English. The lunchtime crowd at Train of Hope is what I remember from Stadion — many Ukrainian elderly pensioners, some eating in groups, some eating alone. They started to wait on the stairs for the used clothing “shop” (it’s donated and free) to open at 2pm, even though it didn’t really seem like lining up was necessary. I figured it must be psychological by this point, when your entire existence feel like a fight against others for resources. The new space is really impressive and I made a mental note to share it again — the opening hours what is available on site — with my Telegram group.

We then raced over to Wien Hauptbahnhof, as we were by this point late on a schedule I had jotted down with sharpie in a notebook a few days prior, having stupidly forgotten to leave any time for breaks or eating/drinking. At the train station, in a McDonalds I used to use as a volunteer to buy gift cards and run to the WC, we met with Vassily, a diabetic from Kyiv who is the administrator of my Telegram group on a voluntary basis, and Anzhelika, a mom of two originally from Donbas but now living with her daughters in Burgenland.

Vassily and I spoke about common questions and problems, and how we try to share useful, relevant information within the group, while also managing any conflicts which sometimes arise anytime you put 2000+ strangers together online. Teri then interviewed Anzhelika by the trains. Anzhelika wanted to explain about what happened when she went home to Ukraine for a week, to get some documents and see her husband. She had gone with her older daughter, left her younger daughter behind with a responsible adult guardian, and warned their NGO landlord about the upcoming trip. Nevertheless, she and her older daughter were still de-registered by the authorities and spent the next month trying to reinstate themselves. The authorities knew about the trip, but in a Kafka-like manner, explained “rules are rules” and if you are gone for more than three days you must start over. Anzhelika also told us how she and her daughters took a three day trip to Prague, and also lost their payments for those days. This morning, I read in the Austrian-Ukrainian Telegram groups that local police are doing home checks of Ukrainians and they are searching the database of international border crossings and reducing benefits for days spent “abroad”. Which just makes me want to bang my head against the wall when I think abut all the money that is spent on the “enforcers” rather than putting money in the hands of those who need it the most. It’s maddening.

Vassily is a great example of a highly educated Ukrainian who is not able to navigate his way to decent employment and stability because of the Austrian system for Ukrainians. At one point while we are filming, his insulin monitor goes off, and he injects himself with what looks like a small Epipen right there in McDonalds. Vassily speaks perfect English, nearly completed a PhD, and has a visa to Canada, and is really thinking about going, but trying to make sure the mathematics will add up. What if he cannot earn enough to support himself and his mother? In Austria, they were essentially made homeless several times in Upper Austria, at which point a woman on the street gave them my phone number. They contacted me, I put them in touch with a kind Austrian who helped drive them to Vienna and register them here, and then they were able to find a room in Vienna. But if Vassily gets a job, they will lose what small payments they do receive, and he will have to calculate if they can still afford rent and to feed the two of them. He is also worried about his healthcare if they go to Canada. His diabetes is being cared for well in Austria. However, he explains, what if I get a job and do well and then in March 2024 Austria says we all have to go home? What then?

We are by now high on coffee but very late for our next appointment, which is arguably the most important, with the poor and traumatised residents of Haidehof, which I have been writing about for nearly a year now. In February, over 60 residents of 200+ Ukrainians living in this dorm (former nursing home), where they are “fed” and only receive a ridiculously low €40 per month in pocket money to cover all of their expenses, signed an open letter to city of Vienna authorities demanding better living conditions. The result? The city has decided to close the dorm entirely by April 15 and has promised, at least verbally, to rehouse the residents in various addresses across Vienna. However, those who worked on the letter and gathered signatures, those vulnerable residents who were the loudest (a blind man, an older woman lung transplant / cancer patent, a man with a brain tumour in a wheelchair), they have not been assigned housing yet, and were visibly traumatised and scared when we met them yesterday. They fear they will be punished by the power trip of small bureaucrats who yield huge power over very vulnerable people and worry they will be kicked out with nowhere to go. I tried to reassure them this will not happen, but they do not believe me. They do not trust anyone anymore. You can’t blame them.

We arrive nearly an hour late and they have been waiting in the cold wind. I feel awful because the one thing I always try to do is arrive on time. I apologise profusely and Teri asks the local Penny store if she can film me buying a €50 gift card there. I need to give it to a mom from Mariupol who is due to give birth in June and is waiting for us too with her mom, her toddler, and their adorable dog Ksenia they adopted from a circus in Linz. The store says no. Teri looks upset. I explain that is Austria. I never expected them to say yes.

The hardest conversation is next. There is a group of six or seven Haidehof residents. They have to choose who will talk and I will translate. In the end, it is Natalia, a highly educated woman from Odesa who is a cancer patent and had part of her lung removed here, goes to rehab an walks with a walker, whom the residents want to speak for them. Another older woman pulls me aside and thanks me for giving her a card last summer. Her face looks vaguely familiar. I cannot possibly remember everyone. A tiny woman probably around 70 with no teeth pulls my coat and whispers: I received a KLIMABONUS. I smiled. To her those €500 were probably the most money she has ever received in one go. She moved to a new address yesterday. The moving van cost her €40. Where did you get €40 from, I asked, disappointed but not surprised that the city of Vienna and NGO on duty are not helping residents with their physical moves and transportation of their personal belongings. She whispers with a cheeky smile: I clean the floors in a Turkish hair salon. I hope they pay you in cash, I ask gently. She smiles again. Just amazing.

Teri sets up a shot of her interviewing Natalia, standing with a walker and her hair covered with the kind of head covering cancer patients wear, and one one side of her is Ihor, a middle-aged slim blind man in dark glasses with a yellow blind badge on his black jacket and the other side, Artem, who is in his 50s, in a wheelchair and I learned only yesterday has a brain tumour. I text often with Artem because he writes me over Telegram with requests for Hofer cards for new dorm residents. He always sends me a photo, full name, and birthdate. And sometimes I have to write him back and say they already received a card, and then he is upset other residents tried to “trick” him. But you cannot blame them for trying. And I feel terrible for having such rules but raising funds for cards is so hard we simply cannot repeat so in fairness I stick with one card per family, one time.

Natalia begins talking about how they all feel mistreated and unheard, how when they ask for help whether it be with translation or medical appointments or legal advice, they are told to sort things out for themselves. Artem adds he was asked to sign documents in German he couldn’t understand. It was a heartbreaking scene again the backdrop of this terrible dorm of a year’s worth of pain and trauma, and yes, desperate poverty. She starts crying as she tells Teri she is terrified they will be made homeless next month and kicked out on to the street, as punishment for having dared to speak up in the first place. It is cold, the wind is blowing, I thank them for their time and apologise again for having kept them waiting. I see my words also don’t help anymore. They are heartbroken and disappointed and don’t trust anyone anymore. Natalia pulls off into a corner and sobs. Some of the other women and I try to console her. They walk back to the dorm, crossing a zebra crossing, Natalia with her walker, Artem in the wheelchair being pushed by Ihor, the blind man. The other women follow. Ihor struggles to push Artem over the curb. They stop and try to help. It is such a sad scene and Teri asks the cameraman to shoot it from a distance. I turn around a have a quick cry like I so often do when I leave Haidehof. It is a haunted place.

Our last outdoor shoot is me trying to put envelopes in a mailbox across the street. It was so cold and windy I kept thinking I hope this is it: but it was not it. Teri said we needed to do an “exit interview.” So we opened Google maps and found a new pizzeria which likely served decent pizza but surely existed for money laundering purposes (I heard my father’s native language, looked around at the plush velvet chairs, and it all made perfect sense). Thankfully, the pizzeria agreed to let us film inside. It was 5pm and we were alone until a kids’ birthday party showed up.

The exit interview was perhaps the hardest part. I was tired, as an introvert used to having down time, alone with my thoughts and my phone, and was processing the emotions of the day, thinking about what I was supposed to say to questions like Ihor’s, who pulled me aside and asked if I can help him find a doctor to restore his eyesight. The doctors he has seen so far had sent him off with no promises of additional treatment. I was sad that in nearly a year of writing about Haidehof nothing really got better until they finally decided to close it and even now not all residents have received housing assignments.

Teri kept driving the exit interview conversation back to me, which made me uncomfortable, because I see myself as a vehicle. A vehicle who can deliver cards, communicate with Ukrainians, and share their stories. A vehicle to raise donations, cards, and funds to deliver more €50 supermarket gift cards to Ukrainians in need. And I never know what tomorrow will bring. I always look with a tinge of anxiety at my inbox, never knowing what drama awaits me next. As we sat there, I received a text from a fellow volunteer about an American soldier wounded in Ukraine, his leg might have to be amputated, and how could they access a foundation or donors who could help finance his recovery? I didn’t have an answer. I replied try the NAFO people.

Last night I had a long subway and bus trip home, and I had so many new messages. When you deliver twenty cards in one day, as we did yesterday, you receive forty new requests. That is how the Ukrainian grapevine works. So today I will be going through those many messages, explaining we have a long wait list, and trying to give priority to women with children and the elderly in the arrival center. I hate having to make such choices but I know you must set clear priorities when you have limited resources.

If you are in Austria and would like to email me Hofer gift cards, they are now available for purchase online (unfortunately you need a local credit card billing address). To donate cards to me directly, any supermarket chain or even Klimabonus/Sodexo vouchers, they just need to be €50 instalments, please send me a message for my address or to meet up with me. For those of you outside of Austria, PayPal works to send me funds which I use to buy cards here and deliver them. The first recipients will be in the Arrival Center, where I am frankly very worried Austria has decided to quietly stop giving out any permanent social housing assignments, keeping refugees living on cots and showering in a container in a courtyard, for weeks and months until they simply give up and decide to go back to Ukraine. I will finish writing this and go back to my envelopes. I worry the list is several dozen deep by now. Lilia the doctor wrote me late last night and asked me not to forget about her 17 year-old son. Others have the false hope I can help them find work. I worry how to correct that. Heavy.

I wish so much for simple honesty and truthfulness from the authorities, both state and NGO, responsible for the refugee response, who unlike me do receive salaries and are clearly (amazingly) not troubled by guilty consciences. If Austria is closed, and no more social housing will be handed out, it should say so openly. If the labor market is essentially only open to those who can afford to rent private housing (three months’ deposit is the norm here), say that to Ukrainians in Ukraine before they pack up and come here in hope of economic opportunities which are not waiting for them. The global west needs to focus much more attention on helping Ukraine’s war economy and helping maintain viable employment in Ukraine.

Finally, a huge word of thanks to Teri, who worked a never-ending day and took a flight home last night on which she still had to file another story…I sat there in awe of her stamina and passion and dedication to her work. A true inspiration.

Thank you so much for reading and for making all of this possible for so many months already. I will share the video link as soon as the story is ready!