Chernobyl

A very long day inside the Chernobyl exclusion zone: Zalissya, Radar Duga-1, Kopachi, the former nuclear power plant, model Soviet city of Pripyat. Plus very friendly wild dogs, lots of them.

This morning started at 6am and still hasn’t ended. I suppose day trip to Chernobyl isn’t something you are supposed to emerge from full of energy, but I feel totally drained, emotionally, physically, my head is spinning. So much new information, so many things in the present I began to see differently with a better understanding of the not so distant past. It’s like a sensory overload. I’ll try my best.

My Bolt driver had a Central Asian first name, spoke perfect Russian, and was playing Ukrainian morning radio. The song was literally “good morning Ukraine” in Ukrainian; they sang about coffee which is kava and reminds me of Serbia and then I get all sorts of confused. When all the Slavic languages start melting together you know you are in trouble. It is incredible though how basically everyone I’ve encountered in Kyiv is some level of trilingual: Ukrainian, Russian and English and no one things that is anything out of the ordinary. They just switch back and forth like the whole world does that. It’s amazing to hear.

At 7:30am we met our guide and drive by a microavtobus as they say in Russian. The tour was supposed to be in English, but the other six guests who showed up all had Ukrainian passports, so the guide asked if we would agree to do the tour in Russian, and that was that. The law in Ukraine is such now there are only two official languages: Ukrainian and English, which means tours can be done in Russian for private groups, but cannot be officially advertised as a service. There are so many layers to every onion. Each day here it feels like I peel back a few more, and yet it also feels like I could peel for 50 years and never fully understand.

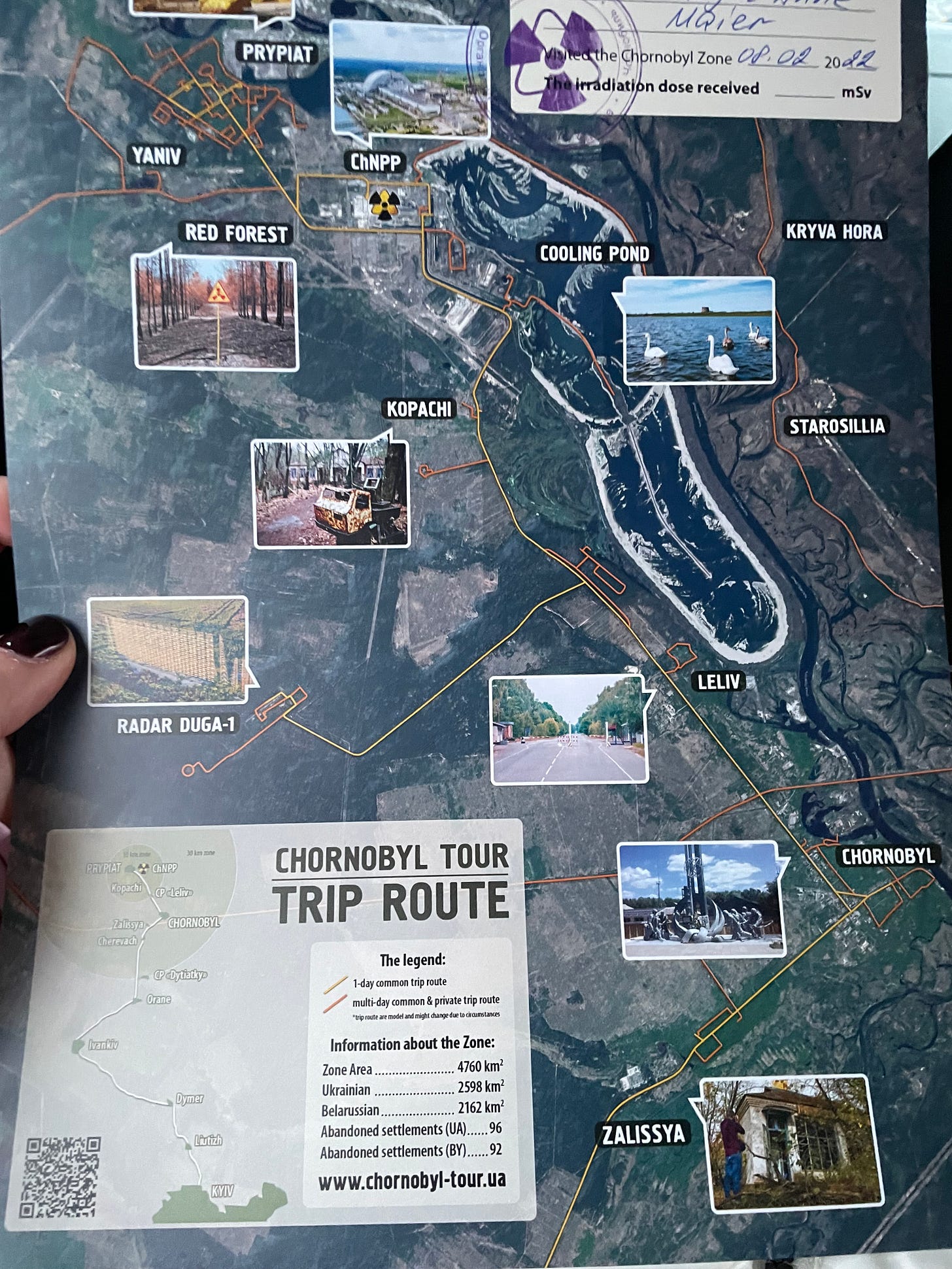

Our guide Daria from Chernobyl Tour was amazing. She began by handing us all a map:

We drove almost two hours out of Kyiv, along that same northern, rather depressing highway, past relatively flat but sometimes forested ground, until you reach the first checkpoint. While we were driving, Daria told us a lot about Chernobyl, and we watched clips from a documentary about how the robots failed and 3,828 men were sent in instead to hurl madly radioactive graphite off the reactor roof in two minute shifts. You probably remember that scene from the HBO miniseries (more on that at the end…Daria had many feelings about the show).

In recent news, Daria explained that on February 4, the Ukrainian government thought it would be a brilliant (sarcasm) idea to have army shooting practice and drills in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, with the assistance of some foreign government military advisors, and totally forgetting about the fact that what’s in the zone should, in fact, be seen as a museum of sorts. (We did see bullet holes in the broken glass windows of some buildings in Pripyat from the shooting a few days ago. Insanity). She was really mad and rightly so.

A little bit of background: the Chernobyl reactor number 4, the site of the accident which occurred at 1am on April 26, 1986, is now covered with a 36,000 ton cover made of two layers of super thin stainless steel that is supposed to last 100 years. The EBRD helped fund the sarcophagus project, as the Soviet post-accident solution was patchwork and looked a bit like lego with gaping holes.

People still live inside the exclusion zone, in the town of Chernobyl, which itself was once a large Jewish town hundreds of years ago and is the birthplace of Hasidism. The town itself is pretty sad looking, houses workers who work two weeks on, two weeks off. It still has a curfew of 10pm and no one can buy alcohol past 9pm (although you can buy as much as you want at 8:45pm).

Many of the buildings in the villages and cities that were evacuated after the accident are now really falling apart. For years, in addition to officially sanctioned tours, people have snuck into the zone for all sorts of reasons. In Russian, our guide called them “Stalkers” but not in the English sense of the word. In summer they often use the river to enter the zone. One stalker from Belarus died tragically after climbing up the giant Duga radar and then falling off. Part of the problem with stalkers is they go into unstable, abandoned buildings and now roofs are caving in, ceilings crashing down, and floors just breaking apart.

That swimming pool many of us have seen photos of? Can’t go there anymore. The roof of the gym collapsed. Daria explained there is an effort by conservationists to get funding to preserve what’s left inside the zone. With restoration, they are hopeful many of the buildings of interest can still be preserved safely. But the clock is running. And with Putin’s tanks just over the Belarusian border, who knows when preserving the crumbling buildings of the zone will be a government priority. Sadly, I doubt anytime soon.

Daria gave us a crash course on radiation: alpha (few centimetres), beta (several meters), gamma (the one you can’t escape). The only message I really understood was don’t touch anything. We would be inspected on our way out of the zone with Soviet machines that look like a joke but apparently actually work (we all passed so I wasn’t able to verify this firsthand; the machines didn’t look very convincing to put it politely).

So how did a nuclear power plant end up in Chernobyl in the first place? In the 1950s, the Soviet authorities realised that 1 kilogram of uranium could produce the same amount of energy as 1 million kilograms of coal. The first “test” reactor was opened in Obinsk, Russia. Although it wasn’t really much of a test. As Daria explained, the pressure to ramp up capacity to produce electricity using nuclear energy was so great that new plants were opened without adequate testing or even scenarios for what to do should X go wrong. There were problems at Chernobyl before and after 1986.

The location was chosen because it was a sparsely populated area, forest so would not be taking away agricultural land, and there was plenty of water: each reactor (there were four with a fifth in construction when the accident happened) used 40,000 cubic meters of water. The largest artificial pond in Europe was born.

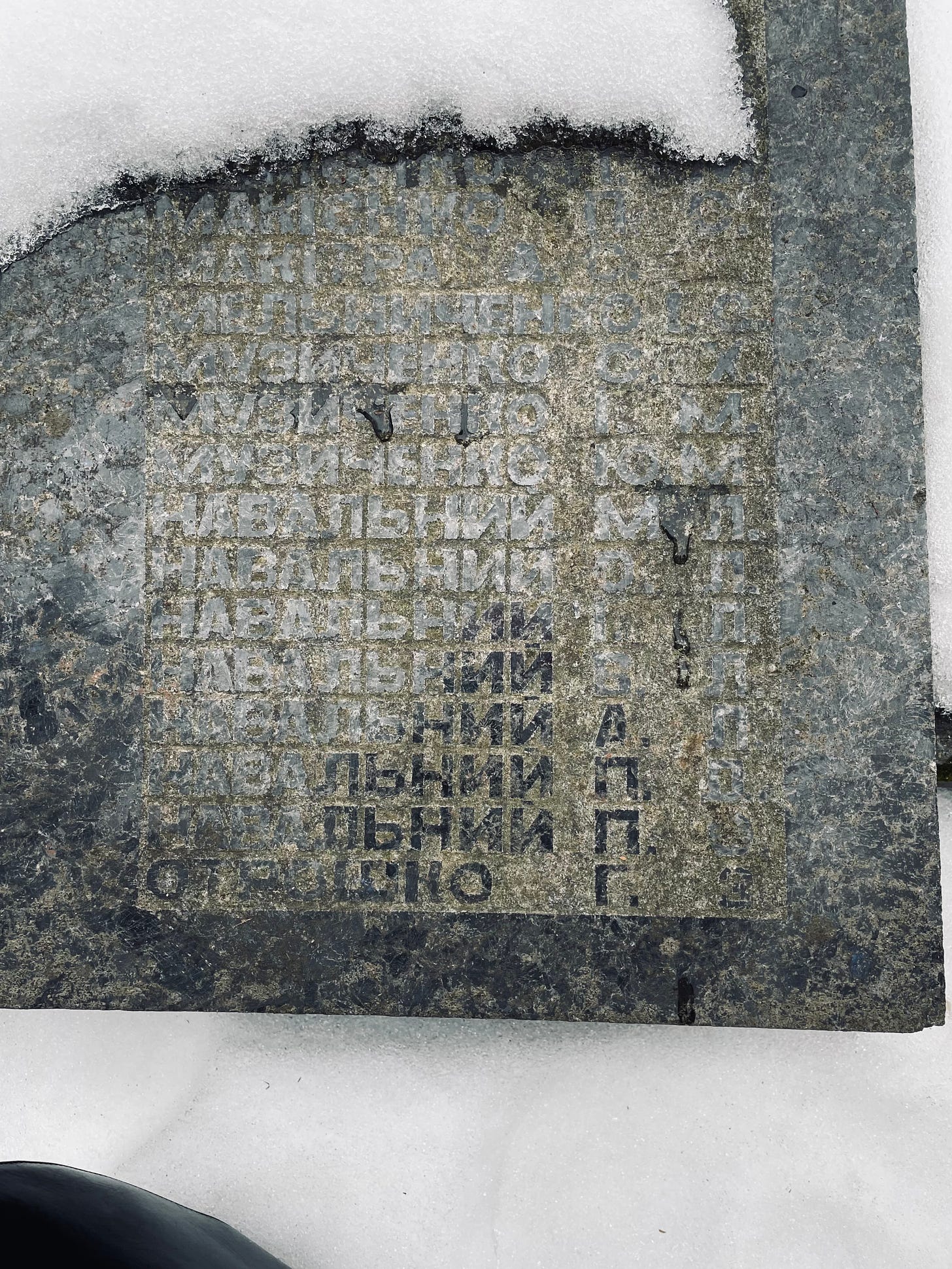

Our first stop after the checkpoint was Zalissya, a once prosperous collective farm village pop. 3,300 that used to be the home to some of Alexey Navalny’s relatives. I was really surprised when Daria wiped the snow off this Great Patriotic War monument, because it all clicked into place for me. In the new documentary film about Navalny, he speaks about his own upbringing, says he had family living near Chernobyl, and remembers exactly how the authorities pretended like nothing had happened and everyone was told to go plant potatoes “nothing to see here”.

The village is well preserved, but the glass is broken everywhere. This was intentional, Daria explained, as liquidators were instructed to throw out all the belongings and furniture, and this was done by tossing everything out windows. It was also meant to be a deterrent to keeping people from secretly trying to return to villages within the zone. However, the Soviet authorities proved no match for stubborn elderly people who had survived the Holodomor famine and Great Patriotic War and didn’t see why radiation was a reason to give up their homes and their cows. Many of them even snuck off into the forest and then returned, illegally, to live in the villages. Ultimately they were given amnesty. And somehow, many of them survived.

The rural villagers, Daria explained, were resistant to being told what to do by the Soviet authorities, while the residents of Pripyat, the Soviet model city near the power plant, which was the employer of 70% of the town’s residents, had no reason to question the system that had been good to them (high salaries, spacious apartments in a brand new development), and calmly got on the buses, thinking their evacuation would only be temporary, like an extended holiday.

Our next stop was the giant Duga radar. I’d seen the photos on Instagram but honestly didn’t really know what it was all about. Daria explained, using a stick in the snow to draw a simple diagram. Back when the Cold War was still a thing, both the U.S. and Russia wanted to build systems to be able to know if missiles were flying at them. The giant Duga was meant to catch waves way up in the atmosphere, thereby giving the USSR a whopping 30 minutes in the event of the worst case scenario. Only there were two problems with this: first, Duga only worked 30% of the time due to it having to stretch over the North Pole (stormy) to pick up whatever it was listening for, and second, even if they had 30 minutes notice, the Soviet joke went, the only thing anyone would know what to do would be to turn it into a drinking game. Like so many Soviet projects: “we wanted the best and it turned out like always”.

The building looks like this on the inside, with little painted drawings of American nuclear weapons and handwritten calculations of their speed and other parameters. Totally completely scary stuff. There was an entire closed town on site built for the military staff and their families serving Duga. You can guess who was evacuated first when Chernobyl happened, despite radiation there being far lower than in many other locations.

You can see from this picture that when you visit the zone in February, you are basically walking on snow on top of solid ice. We walked several kilometres today and it was really, really hard on such terrain. I of course had the wrong boots because I didn't want to ruin my nice boots. It was kind of embarrassing and I slipped a few times. I was the old one in the group. Surprisingly, most people looked under 30. I guess it appeals as well to people too young to remember the USSR, or born after it fell apart.

There were two very cute puppies eating out of a giant bowl by the main gate. Stray dogs are everywhere in Chernobyl, but they are friendly, well fed, and somehow give the depressing place a bit of life.

Next, we drove to the former Chernobyl power plant itself. You see the giant dome from a distance, and many of the buildings you cannot photograph as they are now under surveillance of the SBU (the Ukrainian FSB). On the side of one of the original buildings is a sculpture of the “Peaceful Atom” which our guide explained was a complete Soviet myth.

Daria tried to explain to use what happened that night in Chernobyl. My technically explanations are absolute rubbish, but the less technical stuff made perfect sense so I’ll try to recount. On April 25, Chernobyl got a call from Kyiv. Kyiv asked Chernobyl to delay its scheduled tests until that night shift, because there had been a problem at another plant somewhere else in Ukraine and therefore they needed Chernobyl to keep producing at normal capacity until night. Fine. The night shift arrived, and was asked to do the test even though they weren’t the team usually in charge. They began the test, but when things went wrong, not only were there no actual instructions what to do if things go wrong, but the solution to hitting “stop” entailed actually speeding things up before they slowed down.

Daria used an analogy as if in order to stop your car, every time you hit the break, it accelerates for five seconds before it slows the car down. Not exactly ideal. So that is what happened that night. Hitting stop made things heat up so much it exploded. But unlike the HBO presentation, the explosion wasn’t mega loud and people didn’t come to watch from the bridge in Pripyat. Apparently the people working in reactor No. 3 next door initially didn’t even know anything had happened.

The last part of the tour was for me personally the most incredible. Pripyat was built in 1970 as a model Soviet town. Heaven on communist earth. It housed almost 50,000 residents in 1986, most of them young, all of them Communist Party members, and the vast majority of them working at the plant. Salaries were high, the town had everything: restaurants, swimming pools, a well-stocked western-style supermarket (a rarity), a river beach.

What was once a model to Soviet planning is now overgrown by trees, run by dogs, and many buildings are starting to crumble. The photo at the top of this post is from one of the schools. You’ll spot the date: 1985, forty years after the end of the Great Patriotic War.

You probably remember the hotel from the HBO miniseries. The roof is now caving in. It wasn’t a hotel in the sense of the word we use today. Ordinary people from Kyiv could not come for a weekend, but dignitaries and communist apparatchiks would use it for official visits. Across the square was the palace of culture which hosted weddings. Six weddings were hosted on Saturday April 26, 1986, after the explosion took place. One was even a non-alcoholic wedding, as couples were incentivised to have dry weddings in exchange for getting bigger apartments (people in Pripyat were well paid and the authorities were worried the young professionals were drinking too much).

The supermarket blew me away. There were no supermarkets in the 1980s in the USSR. Even in the 1990s Moscow there was that awful three-step system to ask for what you want, find out how much it will cost, go pay that amount with a cashier, and then carry your receipt back to claim your item. Terrible. Today, the dogs have taken over:

The last parts of our tour were the amusement park, the Ferris wheel that never actually went into operation, as it was scheduled to open on May 1, 1986, and the also never-used football stadium. A match was scheduled for that morning of April 26, and instead of the opposing team showing up, a helicopter landed. Thus, the football players were amongst the first of the city’s residents to learn something was amiss.

As we drove out of Pripyat, Daria showed us where they had made target practice a few days before. I could not believe it. We then talked about the aftereffects of the disaster. To this day, Belarus lost the use of one quarter of its arable land.

A nearby village, Kopachi, had radiation levels so high that people were vomiting and suffering diarrhoea. They knew something was wrong. They wanted to leave. They tried to flag down the empty buses that had been sent to Pripyat but were leaving without passengers, as some had stayed on to help at the reactor. 62 empty buses passed by the villagers and refused to drive them out of the area into safety. Orders were orders, and the buses were only designated for Pripyat. More than ninety percent of the village residents of Kopachi died.

On our long drive back to Kyiv, I kept thinking about what a mess Soviet leadership actually was, how a culture of yes-men and insecurities and overachieving led to a situation that could have killed millions more than it did, due to the heroism of a few individuals who found themselves in a terrible place at a terrible time and tried to do the right thing, sacrificing their own lives in the process. I feel like I am travelling backwards in time, having started yesterday with seeing the corruption of the post-communist era at the Yanukovich residence, and today moved on to trying to get a better of understanding of how Soviet management worked in practice. Incredible mathematical and scientific knowledge did not always transfer into real world results. There was always, as Daria said often today, a human factor.

Just like now, there is always a human factor. Not once did anyone on our tour, a group of about ten of us, mention the words Russia or Putin. There was not a single word about an army of tanks and soldiers very close to where we were today. I didn’t bring up the subject independently, but I think it’s important to state quite openly I don’t feel panic. Now that might be because people are used to a great amount of uncertainly in their lives (after all, Ukraine has had about six presidents in the time that Russia had only Yeltsin and Putin), and it might also be that few believe it would actually happen. I continue to feel like the internet and real life have diverged, massively.

Should Putin have isolated himself into thinking that Ukraine will welcome him with open arms, I fear he will be proven very wrong, very quickly.

I have seen over just a few days how proud people are here, how it is not Russia, it is something entirely different, a very special mix of cultures, with its own history. I hope the world will give Ukraine support and space to breathe, that means support that doesn’t come with a thousand strings attached.

There is still so much work to be done here. This entire part of the world went from Austro-Hungarian / Russian empire to Soviet Union to total destruction and holocaust of the Second World War to rebuilding and then dismantling of communism to picking up the pieces of thirty years of crony capitalism and massive corruption, all while trying to fix up what the Soviets built that is now falling apart. Not an easy task.

No one has time to deal with a Russian invasion right now. People have actual real problems, as do local and regional governments. Perhaps one of the biggest lessons we can all take away from the tragedy of Chernobyl is not to bite off more than you can chew. The nuclear power plant should never have been rushed into completion before there were proper tests and a plan for what to do when things go wrong. As our guide explained, if it hadn’t happened that day, it would have still happened eventually. Only a matter of time. So humility and recognising one’s own limitations. A very timely message.

For more photos see my Instagram or this Twitter thread.

Hallo Tanja, danke für deinen tollen Reisebericht! Interessantes zum Begriff "Stalker": Er stammt aus einem Buch/Film: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roadside_Picnic