First impressions of Kyiv

The second in a series of ten posts about my recent short trip to Kyiv.

It was early Saturday evening by the time I swelled a giant ibuprofen pill, washed down with a tiny bottle of “kids’ water” sold at the pharmacy on the corner next to my hotel. My next target, before thinking about a hot meal, was acquiring a local SIM card. I walked through leafy, hilly streets, past the Golden Gate (the photo below was actually taken the next morning but gives you an idea of the square), towards Khreshchatyk, Kyiv’s main thoroughfare, and the way towards Maidan. For context on everything that happened in Ukraine leading up to and during 2014, I would really recommend Christopher Miller’s new book, which really wonderfully dives into the myriad of nuances necessary to fully get your head around recent Ukrainian history, much of which he witnessed and reported on firsthand, should you want to learn more.

Google maps had promised me a Vodafone shop right in the mall underneath Maiden, so I headed in that direction. It was hot, and there were many young people out. I walked past packed cafe after cafe offering a range of food from sushi to Georgian to cakes and coffee, each with a smattering of outdoor tables, all busy on a warm Saturday night. The first thing I noticed, having interacted with Ukrainians for a year and a half now, but in Austria, was the presence of men. There were young men on the streets. There were also many men in uniform — of all ages. It appeared to me that military even on their days off were walking around in the same khaki colors Zelenskiy is now famous for wearing. Perhaps more so than in winter (my last and only ever visit to Ukraine in the past was in February 2022), I was acutely aware of my own age and outside appearance as I walked by woman each more stylish and beautiful than the next, all dressed elegantly in variations of summer dresses, blouses and skirts. Ukraine is not the place for a woman to go if you want to feel good about yourself. You look around and feel like you were not blessed in the same way via the genetic lottery. Even older woman had dressed up a bit — no athleisure in sight. Shops are open late, restaurants are all fairly busy, plenty of people walking around. It feels totally surreal because here you are, just arrived to a country at war, and yet, it doesn’t look like that. Not until you start to take a closer look. By the end of the trip I realised the normality is more of an illusion, but certainly Kyiv feels safe-ish, and as local residents later explained to me, it as the capital benefits from the best anti-air protection capabilities in the country. In short, residents say they sleep more or less fine at night. More or less.

I turned left onto Kreshchatyk after walking down a rather steep hill (a big difference from central Moscow which is essentially flat, and I apologise in advance for these comparisons, but I cannot help but make them, having spent so many of my formative years in Russia’s capital). The wide boulevard is a classic symbol of the Stalin era, when grand, imposing buildings were built in the post-war period on either sides of ridiculously wide roads. The kind of roads for parades. It was nearing sunset as I approached Maidan, and I took the underground passage under the street to the underground shopping mall. The kiosks sold t-shirts with logos like “Putin is a dickhead” and little stuffed animal versions of Patron the dog. In the mall, I asked at the very modern grocery store chain (Novus open 8-23 every day) for a SIM card, and was sold one at the cigarette counter for about €4 for a month of calls and more than enough internet. I then realised I had brought an android pin, and it did not fit in my phone. I walked over to a phone retailer in the same mall, and the staff helped me switch my SIM and activate it free of charge. Next to the cash register, they were selling salt from the famous mines of Bakhmut / Soledar.

In these encounters like at the phone shop, I was self-conscious at first, speaking Russian, being answered to in Ukrainian, and then continuing in Russian because I cannot offer anything else. I never had an actual problem, and the older the person, the more likely they were to be fine with speaking Russian. Sometimes, I could tell a young person only speaks Ukrainian, and I would offer to switch to English, should they not want to hear me speak Russian. To be honest, I did not sense a problem with languages. You hear plenty of both languages on the streets. Many people, even young kids, are speaking Russian to each other. Beyond geographical splits (broadly speaking, the east and south of Ukraine speaks Russian at home, the west and center, and especially rural areas, speak predominantly Ukrainian), you have to remember Kyiv is now a mixture of everything. People from villages who came in search of work, IDPs from parts of Ukraine now occupied by Russia or near the front lines. I also heard a bit of English on the streets. I overheard a few drunk westerners talking nonchalantly about stopping by Odesa and Kharkiv, and the idea of war tourism left a pretty terrible taste in my mouth. I kept reminding myself I had come not to curiously stare, but to share what I learned, to put my own volunteer work in perspective by learning more about the situation on the ground in Ukraine.

I emerged from the underground mall with full connectivity and paused on Maiden at the flags. The flags, a sea of thousands and thousands of flags, each left in memory of a solider killed in the war with Russia. I made a video but even it does not capture just how many there are. And not just Ukrainian: American, Georgian, Armenian. It is a very somber sight and you see people coming to pay their respects. A reminder that even though life looks normal, it is a mirage. Just hundreds of kilometres away, a full blown war is being fought, and rockets and drones can still fall out of the sky on Kyiv.

As you walk down Kreshschatyk, you see young people hanging out with skateboards and music. The zip past you on e-scooters. The bars and restaurants are busy. People are meeting friends, celebrating birthdays, enjoying the good weather. Life goes on. I paused to take a photo of the Putin prisoner postage stamp featuring the head of Ukraine’s armed forces, minister of defence General Valerii Zaluzhnyi.

I decided to look for a bite on the street by my hotel, where I had seen a myriad of outdoor cafes with appetising looking offerings. But first, I stopped in TsUM, and upscale department store I had visited on my last trip. It was nearly unchanged, still selling an impressive selection of designer goods, but the fabulous food court on the top floor was now nearly empty. I wondered if that was seasonal or a result of the war. Despite the “normality” of life in Kyiv, at least on the surface, I still have the impression the very wealthy left. The very wealthy are abroad and the very poor are living wherever they found housing — for many IDPs this is now villages in “safer” regions of Ukraine. Kyiv looked to me like it has been left to the middle class, stoically waiting it out. I did see many posters glued to billboards advertising hostel rooms, with prices per day and per night. In Ukrainian. That was something new. I wondered who exactly they were aimed at: IDPs? Those seeking to work in the capital? Soldiers on leave would go family, and you would not target foreigners with ads in Ukrainian.

I turned onto a smaller street and walked uphill, past leafy parks with plenty of benches and neighbourhood restaurants. The street were busy and the city felt alive. I stopped at a cafe run by the chain Honey which I remembered from a previous visit, and asked for an outside table. I ordered a raspberry lemonade and a burger, which came elegantly served with pickled cauliflower and roasted potatoes. I didn’t realise how hungry I actually was, despite the heat, until I dug in. People kept walking by: families, couples, dogs out for their evening walks, babies in buggies, teens on scooters. It was like a New York City sidewalk on a hot summer evening, minus the small of garbage. At 9:45pm I asked if I might order dessert and was told they would be closing soon. And then I remembered: curfew. Curfew is midnight to 5am in Kyiv (11pm in Kharkiv), and that means staff have to be able to close up and get home on time. So nightlife starts and ends earlier. I paid about €12 for my meal, including a coffee. I went back to the hotel and turned on the TV, out of curiosity.

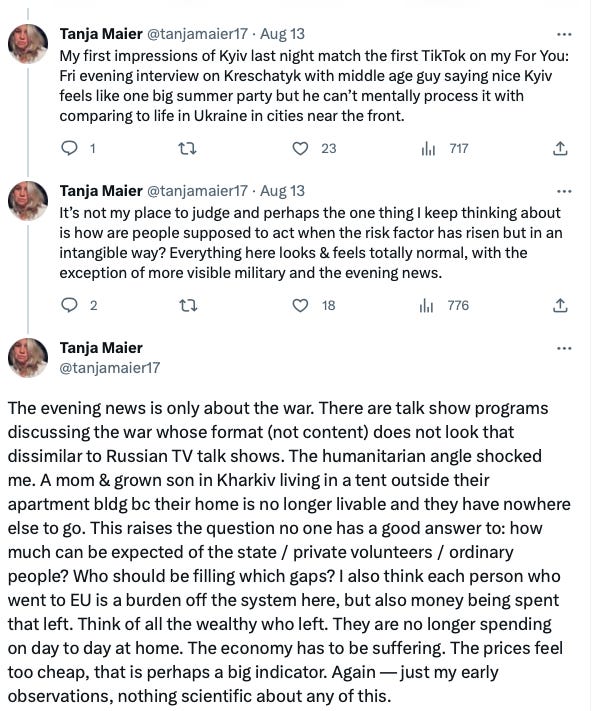

The TV genuinely surprised me. A newscaster reported war news after war news in Ukrainian in front of a Ukrainian flag flying behind him on the screen. He looked photo-shopped onto the scene. A series of news items which left me more unsettled: numerical statistics on the number of missiles Russia launched on Ukraine per month, 2023, accompanied by a chart showing how many of those were shot down. Next a report about a mother and son whose apartment in Kharkiv is not livable, but as they have no other housing, they now take turns sleeping in a tent in their courtyard. This kind of report on national television made me upset — surely with all the aid that is being given, temporary housing could have been found for these two people, and at least incorporated into the report as a happy ending? Next a feature on a soldier who lost both legs, received prosthetics, and his wife now gave birth. The happy new father greets his wife at the maternity hospital with flowers and holds the wrapped-up newborn (a long tradition throughout the post-Soviet space). Just when I was about to switch it all off, a talkshow program came on, and although the language was different, it looked nearly exactly like the talkshows on Russian TV, and this, frankly, scared the shit out of me. For whatever reason, I felt triggered. I reminded myself most Ukrainians get their news from Telegram channels anyway, and switched the TV off.

The first night was quiet. No air raid alerts. In the morning, I had to go to my local “Nova Poshta” and send all the care packages and documents I had been handed by Ukrainians to send to their family and friends. Nova Poshta is the most amazing business. It is a private company which essentially acts like a “courier” service across the country. You can go there with a package or shopping bag or even a plastic folder of documents, and a little piece of paper with the name of the recipient, mobile phone number, and the number of their local Nova Poshta branch. You hand it all over, the staff member puts it all into the system, you explain who should pay for shipping (sender or recipient), declare the value of the contents, and that’s it, off your packages go, and a day or two later the recipients receive a text message notifying them to collect their deliveries. Amazing. I must have annoyed the young woman working there that Sunday morning (yes, open on Sundays, 9am to 7pm), asking a thousand questions about the business model and even where she bought her iced latte (kiosk across the street — there are coffee kiosks in Kyiv every 50 meters or so).

It was a beautiful morning. The sun was shining, flower seller were selling bouquets by the metro entrance, sunflowers, colourful daisies, and dried wildflowers, bees buzzed around them. It felt too good to be true. Unreal.

I took the subway to my first meeting that Sunday, to interview a young Ukrainian volunteer living in the historic district of Podil to whom I had been introduced by a Ukrainian now living in Austria. I know Podil, having stayed there on my last trip, and love the historically Jewish neighbourhood which has a different vibe than the very center of Kyiv. More young people, more hip cafes, it feels a little bit alternative.

I nearly got lost on the subway because even though the connection is easy, the station had been renamed from Lev Tolstoy square to the Heroes of Ukraine square. I had also forgotten just how deep the Kyiv Metro is — two enormously long escalators. For someone with a fear of heights, you are slightly uncomfortable when it is not packed, when there is empty space in front of you and a deep drop down. I gripped hard to the black rubber railing and focused my eyes on the billboards lining the walls. Children’s drawings in support of soldiers. How to donate towards drones for the army. A lawyer to help you claim alimony. The banal and the new normal, which is anything but normal, blended together. The subways are busy and well used, even on a Sunday morning. Intervals are quick; you wait no more than five or six minutes for a train. The Kyiv stations are not grand, but highly functional. You can change trains in the city center and reach nearly anywhere in the city within an hour. The stations are so deep in some cases (Arsenalna is the deepest in the world) that you must factor an additional five minutes just to ride the escalator down!

I was a few minutes late meeting the lovely Natalia, about whom I will write in the next instalment.

Thank you all for your patience. I received so much information during my trip to Ukraine that I decided I must break it up to do it justice. I also came back to family duties — I have a several hundred kilometre round trip drive ahead of me tonight to bring one teenager to a camp bus in the middle of the night (!). But now having seen just how many people are travelling through the night on buses and cars throughout Europe, it feels a little more “normal” and less daunting. This time, I will pack snacks. I have learned from my fellow travellers in Ukraine.

Again, another wonderful dispatch. I read along with you as if I am situated on your shoulder or stuffed into a pocket as you move through the city. Thank you again, Tanja, for bringing your experiences to us in the wider universe. Slava Ukraini.