Heartaches & Hope

A message popped into my inbox on Thursday evening I could not ignore. I met the family in person on Friday late afternoon. I only found the time now to sit down and share their story.

I have general anxiety every time I open one of the many Telegram messages I receive each day, which range from the banal (could we please have a Hofer card?) to the very dramatic (on Friday evening, when I came home from meeting the family I am about to tell you about, I received a message from a Ukrainian woman whose father had just died and she need information abut burial services to bring his body back to Ukraine). On Thursday evening, I received this message:

“Dear Tatiana, my name is Viktoria. We have been in Austria for nearly a year. We came last April from the south of Ukraine (Zaporizhzhia). Our family is suffering from one more tragedy in addition to the war. My husband needs a heart transplant. In all this time, we have not managed to get an appointment at the AKH (Vienna’s largest hospital which has a renowned transplant team). On February 11, my husband simply collapsed on the street and he was taken by ambulance to a local hospital (Lower Austria — omitting the name on purpose), and there one week later he fell into a coma. They called me and our teenage daughter, told us to say our goodbyes, and that they would not resuscitate him, and I must decide when he should be taken off of life support. I was in shock…he fell into a coma after a procedure which should not have been performed on him, and it was done because of a hospital protocol. So if a Ukrainian wants to live, Austrian medicine cannot help him. My husband survived, and on March 3 we took him home. Today we saw a Russian-speaking doctor, we showed her all the paperwork, she was also in shock. Now they want to send him to a regional hospital (not AKH) for a similar procedure. I feel like they are trying to make me a widow. Now to my point: I need a lawyer (I speak Russian and Ukrainian), my German is still quite basic, or a journalist, or someone who can help. I really honestly have fought for his life, but my strength is running out. I need to draw attention to the situation or my husband will simply die. In Austria we do not have anyone to lean on, we are in a really difficult situation.”

So this is how you go from being the American woman who hands out grocery cards to walking into situations for which you have no training nor competence. I agreed to meet the family the next day at a cafe near where they life. It was a beautiful place, next to an old castle/church in a bedroom community near Vienna. I had been there once years ago to see an outdoor theater performance of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. And now I was sitting a few hundred meters from that outdoor stage, with a Ukrainian family I had only just met, trying to give them advice on how they can fight to keep their husband/father alive. For which I have zero competence other than advice based on my lived experience here.

TL:DR: you need to ask every Austrian you know to pull some strings, try to get into contact directly with the top cardiologists and/or the transplant team at AKH, and you might have more success if you pay once for a private patient consultation with a cardiologist in Vienna who can make a few phone calls to get you into a system that still uses fax machines (yes, really, I have seen the actual fax in the AKH breast cancer clinic and was once told off by a nurse for not having had blood labs sent by fax; the Ukrainian patient I was translating for had them only on her phone in digital form). In short, you need to pull strings, and usually local people can help with that. If you wait for the state insurance healthcare system to get you in front of the right person, it might be a very long wait, as you’ve already discovered.

Viktor is 63 years old. He is tall and stately and says several times in no uncertain terms that he has the will to live and has been on the other side and has no intention of going back there anytime soon. I can see he was once a formidable gentleman before his health deteriorated. Viktoria is much younger, I would guess in her forties, and they have a teenage daughter who popped by just for a minute after school to grab a key to their home. The family originally planned to go to Italy when they fled, thinking just about going “somewhere warm”, but volunteers gave them a place to sleep in Vienna, and one thing led to another, and they ended up living in a small guest cottage without a kitchen of a kind Austrian family who opened their doors last spring in this picturesque bedroom community near Vienna. So Austria it became. They never made it to Italy.

Their daughter enrolled immediately in a local middle school. She is the top student in her class and hopes next year to transfer to a local gymnasium. She is also doing online Ukrainian school in the evenings from 5pm - 8pm via a Polish-American joint venture. She has made friends, both local and Ukrainian, and despite having fled a war and almost lost her father last month, she seems like any teenage girl of this age I 2023: cargo pants, sneakers, headphones.

I ask Viktor and Viktoria what exactly happened at a local hospital in February. They hand me a huge pile of medical papers, all in German, which I cannot read every word of (nor would I understand every word of). We are then joined by their German teacher, a retired professor of history who is now teaching a group of Ukrainians from the local area on a volunteer basis. He sits patiently and enjoys cake and coffee while we all talk in Russian. The discharge papers say something about septic shock cause unknown, but it is unclear to everyone how Viktor suddenly had a temperature of 40C, was essentially pronounced dead, and then took another breath. And lived. After the team of doctors told his wife and daughter that he could not be saved.

Viktor has a bad heart. He knows this. He had what sounds like a cardiac pacemaker/difibrulator implanted in summer 2021 in Ukraine. In November 2022, frustrated by lack of progress being referred from family doctor to specialist to hospital in Austria, the family went to Kyiv and visited the famous Amosov National Institute of Cardiovascular Surgery. The Ukrainian doctors recommended Viktor for a transplant, and the family came back to Austria and translated all the findings into German. But, as Viktoria recalls, local doctors were not really keen on reading them. Instead, they wanted Viktor to write down his symptoms and monitor his heart for 1-2 years before making a recommendation. Viktoria was exacerbated by this reaction. Time is of the essence. Viktor explains he cannot wait for a heart transplant in Kyiv, as air raid sirens mean the bridges are shut, you are waiting for the call and then everything can be called off at the last minute.

The family is singularly focused on Viktor’s health. Viktoria says she did not go to work in Austria because she was afraid of losing health insurance. They receive the social benefits and hand their local landlords over the amount the state reimburses each month (around €300). They are grateful to have a roof over their heads and some money for food, although admittedly it is really hard on such a budget. Viktor owned four stores (produce, automotive parts) in their hometown, he was once a successful businessman, but that is all over.

When Viktor got taken to hospital by ambulance last February, he simply turned blue as he and his wife were walking to their car. She is half his size but tried to catch him as he fell over. Viktoria called a friend who speaks German and begged for an ambulance. The ambulance team immediately performed CPR and took them to the nearest hospital. For five days he was stable, and then his condition deteriorated dramatically, without warning. The couple suspect it was the result of a CT scan with dye. Viktoria explains it should have been done without die. After Viktor came back to life (doctors had told the family they would not resuscitate), the family received a letter recently in the post inviting them to come back to have this same exact procedure performed again, only in a different regional hospital. They are, naturally, completely scared and now solely focused on getting an appointment with the AKH heart team in the hopes that there someone will actually read all of Viktor’s medical files and make a recommendation.

Viktoria is very clear: I am grateful my husband is alive. I do not want to talk about what already happened. But I do want to get him in front of the right doctors who can help him.

She cannot understand why they have not been given an appointment at AKH. When they tried calling the number, they were told something along the lines of you need a referral. But how to get a referral when no one gives one? Is it because of their address in Lower Austria, I wonder out loud? Then she told me the fax story, and I remembered what you are up against as an outsider trying to break in. Viktoria shows me how she found using the internet the head of the AKH transplant team. Later that evening, I send her the team’s email addresses. A little googling and this isn’t information hard to to find. But just emailing the surgeon isn’t going to get you an appointment. That’s not how it works. But what she really needs, and I explain this, is a doctor to get her into the system. Perhaps a private patient cardiologist in Vienna could help? Perhaps it’s worth spending a few hundred Euros on an appointment just to be listened to for an hour and hear the recommendations of someone who knows the system inside and out?

I am sitting there, it’s getting cold already in the late afternoon, in this pretty cafe in this suburb with a view of a medieval church, and wondering why all the Austrians in this family’s life have not pulled more strings. Did your landlord help? They don’t know who to call. The German teacher began to think out-loud about whom he might call. He is in the Green Party. I got very excited when I heard that and suggested he reach out to none less than the health minister of Austria himself. I also suggested the family contact the BBU, as I know they help organise emergency medical evacuations from Ukraine. This family is, yes, already in Austria, but a heart transplant is after all a very serious thing.

What I did not tell the family because I could not bear to be the messenger of this news is there is surely a waiting list, perhaps very long, for organ transplants in Austria, and a commission surely decides who gets priority, and I frankly don’t know what the odds look like for a 63 year old man. But I think what I heard very clearly on Friday afternoon was just wanting to have a chance to be on that list like everyone else with health insurance in Austria. For the system to work as is promised, at least in theory.

We then talked a bit about history and politics and Austria and Ukraine. We talked about polarized societies and how so many things actually are more modern/technologically advanced in Ukraine but few here want to believe it. I was here once as a tourist, Viktor began, and I laughed, because I have heard this a lot from Ukrainians in Austria this year. And we all agreed being a tourist in Vienna and living in Austria are two totally different experiences. Viktor tells me he sometimes envisions Austria as an old cupboard with moths. I countered with an old apartment, with high ceilings, lots of antiques, looks beautiful at first glance but then you see the moths and the dust. We talked about what a small country mentality means in terms of thinking you are the center of the world. “Globus Austria” Viktor said, and I immediately jotted it down. Globe, as in, you think you are the world and you revolve around the sun, and there is no one else on the planet. I was amazed by how perceptive their observations were about modern Austria (which isn’t as modern as it likes to think it is) having lived here less than a year.

Viktoria and Viktor have been married for twenty years. You see very clearly how very much in love they still are. She is fighting, hard, but she needs helpers because she is trying to navigate a complicated system even most locals do not understand. I make it very clear that I can only share their story as that — a story, and I never know ahead of time what result it will or won’t bring. Awareness, yes, but sometimes that is all. They nod in understanding. I think, as I often do in such situations, how important it is just to have someone listen and care, even if it is just the woman with the grocery cards. They are exceptionally grateful to all the kind Austrians who have helped them along the way, but they are super frustrated not knowing how to better navigate the medical system at this very scary and serious juncture.

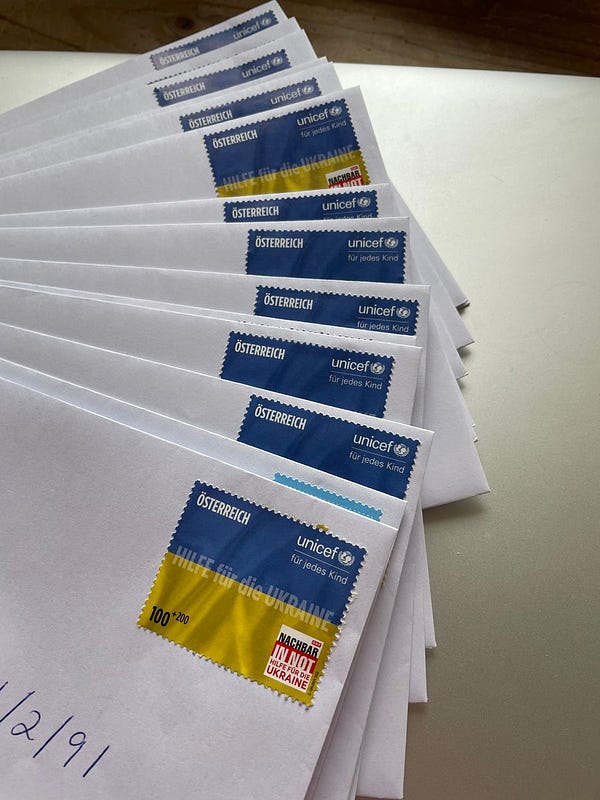

This week I have also been busy with some Hofer card delivery visits to the arrival center (housing assignments are being handed out very slowly and no one seems to know why). More messages from families about to be homeless asking for help to find housing (I cannot be that help) as private landlords are not renewing contracts. And social payments are still being paid out with delays. All of this out of sight out of mind of media and officials alike, imho.

Helped find some funds for an iPad for a student living in a hotel where they are “fed” and bikes for refugees in rural areas. These one-off requests also arrive in my inbox and I try to share them on Twitter. It takes only a few minutes and sometimes produces really great results. Direct aid to those who need it. I am only the connector of kind people with people in need.

If you would like to help towards supermarket gift cards, you can also now email me Hofer €50 gift cards from their website, or donate here towards those I will buy this week. Word of mouth is spreading, and the most vulnerable families are finding me and asking for help. I have also been busy trying to arrange for some filming next week. A TV crew is going to visit me. I don’t want to say more than that now, but this also requires a bit of time for coordinating and planning. I am grateful that there is still media interest in what Mario & I are doing this many months in!

Last night I was invited to a wonderful classical music concert by Valentina. Her son was playing violin in the orchestra (he is also an opera singer!). It was lovely — a young Armenian cellist solo, a young American conductor. Half of the orchestra (with many women performing) is reportedly newly relocated from Kyiv. In short — a lovely evening. But what was truly surreal was Valentina was introducing me to her friends, as she had a few free tickets and had invited a group of us, and two of the ladies looked at me and immediately asked what my last name is, and when they heard it they gasped in shock and said they too had received Hofer cards from me. One had been in hospital for months and had written me, and I had sent it to her by post, so I had never met her. They were all so kind and so joyful at the opportunity to hear a live concert again. It made me a bit sad when I saw the empty chairs in parts of the concert hall and thought those tickets could have been offered to others who cannot afford but would have very much enjoyed the evening.

But you cannot do everything. I at the moment have not yet been able to find a venue for my bake & book sale idea. Maybe there is a message in that. Maybe I should stick to what I can do best. Sharing these stories and delivering the gift cards, and let someone else help with fundraising. Or maybe I should just try harder. Tough call.

This was super long, sorry for that. Thank you for reading and for your continued support, as always.

So happy to read of Valentina and Viktor and the concert. I was just wondering how they were doing, one year on from their arrival in Wien.

"Book and Bake Sale" - what a great idea. Would bring books (English, German) and bake a lot :-)

Sorry for not knowing any location; I'm not into this. If the idea turns into a plan ... you'll let us know, right?

Big hug, Regina