One day at at time

Some long-read/watch/listen recommendations for you. Plus an update from here on the ground.

This morning felt like Groundhog Day, a title I decided not to use for this post because I used it already several months ago. We need a new term for when things stay the same terrible or perhaps get even worse, thinking back to the before times when there was chaos but a tiny hope that with time, things would improve. They did not.

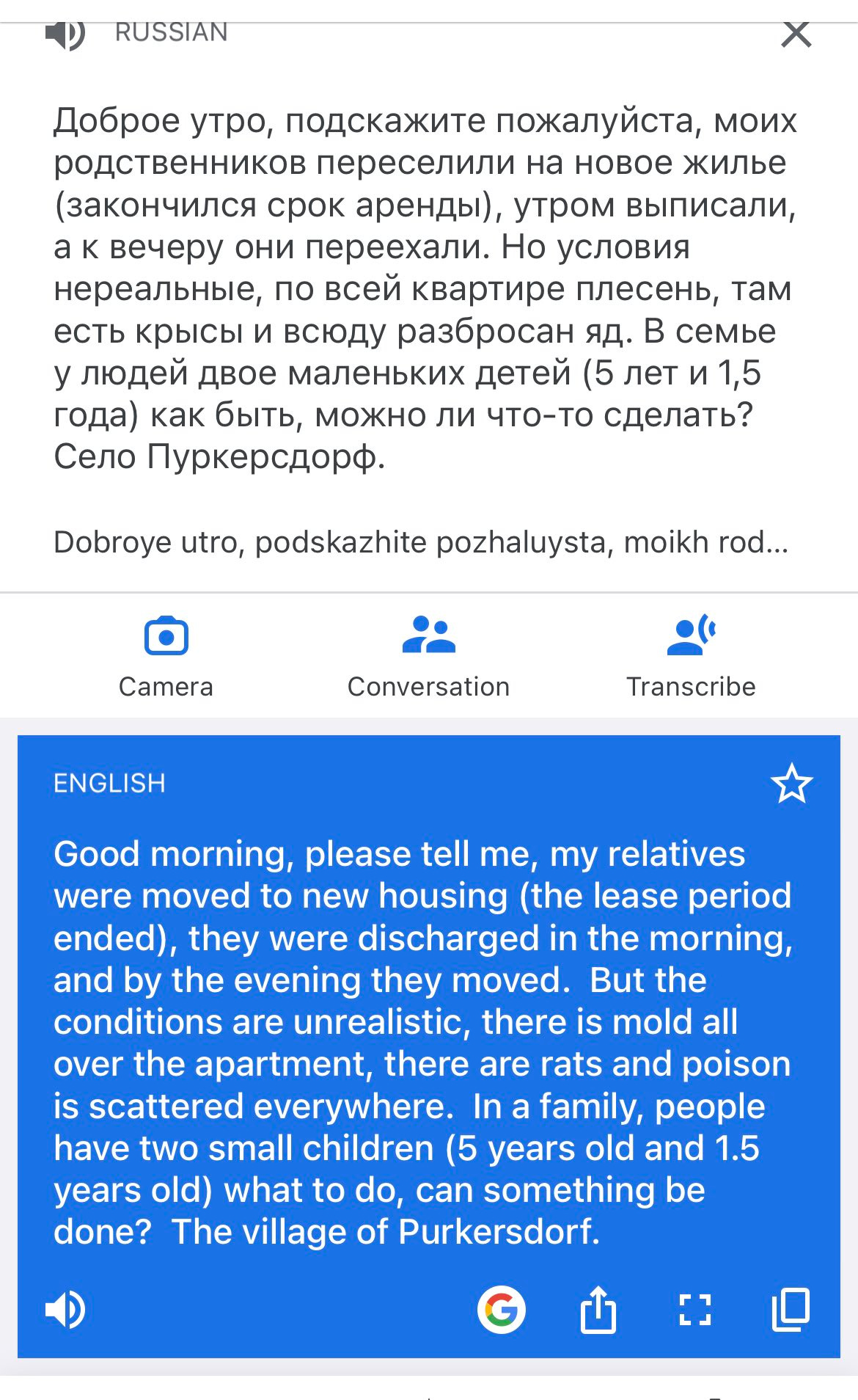

This morning, a Ukrainian mom in Lower Austria posted this in my Telegram group:

A few minutes later, another member of my group posted a series of horror photos from what looked like an apartment: mold, filth, incomplete renovation, a rusty fridge, a not-yet-installed old washing machine. He simply wrote “sounds familiar”. I am not sharing the photos because I have not yet received information as to where they were taken and under what circumstances.

I gave the woman who reached out the contact information of the NGO in charge of “oversight” of social housing for this area of Lower Austria. The problem is that social housing is often outsourced to private landlords, and hygiene standards seem to be, frankly, non-existent. The mother of these two young children then called me in a total panic, wanted me to speak with the landlord of the apartment. I refused. I explained she needs to speak with the organization which sent her family there, tell them the conditions are not ok for two small children to live in, and demand a new assignment. The mother was understandably frightened that if she refused to sign a new contract today, she would be left homeless. I urged her to speak with those in charge at the NGO, but she said the only Ukrainian-speaker was on sick leave and the others only spoke German. So use Google translate, I urged. I also then texted her relative, who originally posted, the contact info of the arrival center in Vienna, knowing full well how unrealistic it perhaps would be for a mom with two young children and all of her belongings to travel back to Vienna and ask for help.

The original poster replies, “I ran away from Austria to Norway, and I don’t regret it for a second, it is like night vs day.” I tell her how happy I am for her.

I then tried to get on with my day without letting myself get too angry about this. I first dealt with urgent texts about literal rats last summer. More than once. And always in Lower Austria. Not surprising this pattern emerges in a state now governed by a conservative-far right coalition, which surely understands if you offer something terrible, some foreigners who sought refuge in Austria will simply return home to their home countries, which is what these politicians ultimately want anyway.

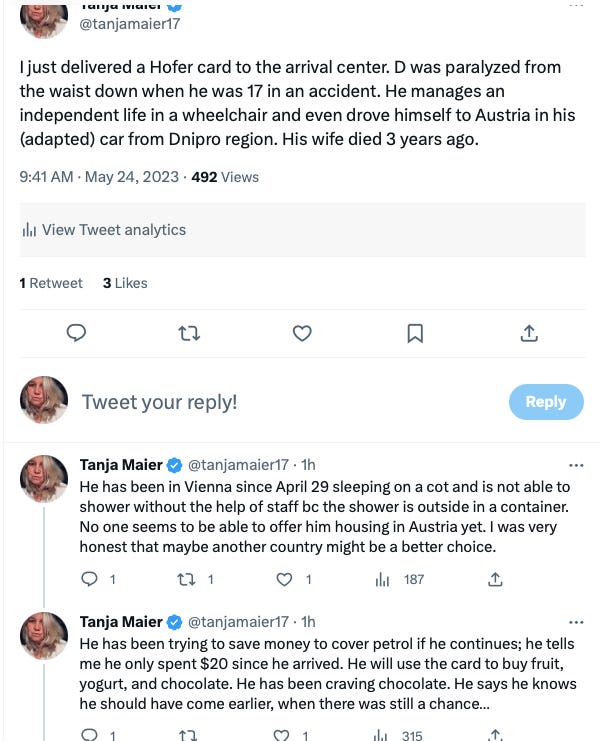

This morning I also delivered one Hofer card to the arrival center. D. didn’t tell me he is in a wheelchair when he wrote me asking for a card, so I waited atop empty stairs outside the (now former but still in use until June 4) arrival center at Spittelau until I turned around and saw a middle-aged man in a wheelchair waiting alone for me at the bottom of the steps.

I feel pretty awful leaving these conversations because I show up with a €50 grocery card, which is much appreciated and offers a little temporary relief, but I cannot solve any of the big, existential problems like social housing or registration or even advise how to navigate a byzantine system. D. admits it took him a few weeks, but he then concluded the staff on site, as friendly as they may be, don’t decide anything. Everything is in the hands of some invisible power which no one can see nor influence. Even we volunteers who have been helping for nearly a year and a half cannot influence city or state governments and their representatives to provide housing to those in need. This topic is no longer of interest to the press, nor politicians. It is a silent, invisible crisis. D. tells me he realized he waited too long to leave Ukraine when he moved around on Vienna’s public transportation network and heard more Russian and Ukrainian than German. I nodded and smiled “there are so many of you here already”. Things were somewhat hopeful a year ago. Not so much anymore.

Thanks to friends of ours who gathered €50 Hofer cards instead of birthday presents at their recent joint 50th party, I am still working with a small surplus, which is why you have not heard me begging for donations recently. Don’t worry, that day will come very soon, I sense. It has been however so nice to be able to respond to requests in real time, something I very much do not take for granted!

I would now like to share with you some of what I have been reading & watching.

This is more than just a magazine article. It is perhaps the single most powerful piece of journalism I have consumed in 2023. I cannot imagine what the journalist went through to write this piece, the risks he took. It also tells an extremely important story about the reality on the front lines which so many expert commentators shy away from talking about. The Ukrainian army today is not the Ukrainian army of February 2022. It has lost so many of those experienced soldiers who did have combat experience. This means seasoned commanders, many of whom also paid the ultimate price, are now having to work with draftees with zero military experience who received a month’s worth of training, if that.

Luke Mogelson, The New Yorker, Two Weeks at the Front in Ukraine

The next reporting I would like to share unfortunately does not have English subtitles (yet), so you will need to understand Russian to watch. Catherina Gordeeva is a fearless one-woman reporter who has been doing deep-dive interviews with subjects in Russia for years. She is a mom of four and her family no longer lives in Russia. She has continued to travel back to Russia and report from there, which I find extremely admirable given the circumstances.

«Государству нельзя сказать "нет"» // «Скажи Гордеевой»

Catherina went to Bereznik, a town in Russia’s far north, 700km from Archangelsk, where a local timber processing plant is the sole employer, and the local man who made his fortune by building that timber business is now responsible for everything in town: roads, infrastructure, even the local hockey ice hall. The ice hall is so special that a successful female coach, Masha, moved from Moscow to coach local youth teams in this far-off northern town, and now coaches a team of Russian grannies. One of them, Valentina Pavlovna, shares her life story, which is something like a history of the Soviet Union and the post-Soviet consequences of that regime.

Valentina Pavlovna was born in 1940. She is on the ice hockey team, worked as a local teacher, rose to school director, and once gave this now famous “mini-oligarch” a loan for petrol when he was just starting his lumber business. He was also once her student. Valentina’s parents were uneducated farmers who were forced into collective farming. They had five children. Valentina remembers going to school without shoes. The family cow provided milk, but the state took the milk away, and what they were given back in return looked like white-coloured water. Her father fought in World War II and returned home. When Valentina was in fifth grade, she walked 15 kilometres one way to a school on Monday, and walked 15 kilometres home on Saturdays. During the week, she and her brother and a neighbour boy slept in the home of an elderly couple. They slept on the floor, in sacks — no beds, no sheets. Valentina recalls these moments from her childhood without emotion. “We were often hungry.” She went on to study in university (she describes her acceptance as the happiest moment in her life, not mentioning the birth of her own three children or getting married, when asked). Her three grown children all left the village, and two of her three adult grandsons now work at “military factories” in Russia. She would not try to interfere, she says, if any of them would be sent to fight in Ukraine. It would be their duty, she explains, to serve their motherland.

Valentina has a work ethnic that would make any manager envious. She wakes up at 4:30 to feed her chickens, and still “goes to work” every day, now at a local organization that helps take care of local “problems” most of which, it sounds like, she is able to help fix by calling the local mini-oligarch who makes the whole local economy run.

Catherina Gordeeva conducts a series of interviews in which she asks the women about the war in Ukraine, about the news they see on Russian TV, and you are left with a picture that Russian propaganda TV has done its job — they talk about the war as an unfortunate thing that had to happen to “defend Russia”, and when pressed to explain if that is the case, why Russia invaded Ukraine first, no one has a good answer. Putin is the good tsar to whom everyone should be grateful for what they do have. One woman talks about her son-in-law who is now serving in Ukraine. He was called up as a veteran of the Chechen wars. Three local men have died already in Ukraine. The war is accepted as an unfortunate new fact of life, a bit like there is snow on the ground for nine months of the year and you cannot do anything about it. Gordeeva presses them all, poignantly asking Masha the hockey coach to explain how she feels about Russia no longer being able to participate in the Olympics like everyone else in the world…the women dance around the topic. It is clear they have cameras in their faces. They are still living in Russia. Their source of income is, indirectly, like so many ordinary Russians, 100% tied to the state. Let’s not forget there is not such thing as truly independent business once an enterprise reaches a certain size, and definitely not in one-company towns.

In short — if you understand Russian, this is a must-watch. A history of Russia past and present in one story of one small town which could surely be multiplied tens of millions times over.

Finally, I would like to introduce you to Ivan Subbotin, about whom I read recently on Twitter and have been chatting with online. I also sent him $100 from Cards for Ukraine because I see the work they are doing in Kyiv is just so important. Many of Ukraine’s elderly are trying to survive on pensions of as little as €50 per month. This is really only possible when you live in the countryside and have your own vegetable plot, or adult children who can help financially. Ivan is a volunteer who together with his team of volunteers is fundraising and delivering fresh produce and groceries to pensioners in Kyiv on a bi-weekly basis. He then posts their photos and stories, with short quotes and biographies (fascinating, and in English!) to his social media. You can find Ivan and read more about his work below; we plan to chat by phone soon as I asked him to find time to give me a brief interview. I am fascinated by grass-roots individuals helping on the ground in Ukraine during this incredibly challenging time economically.

Ivan Subbotin: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter. The social media posts have links to his PayPal account (from which I received an immediate thank you note!).

I was also suggested to follow AlekseevUkraine who is helping single mothers and internally displaced families in Zaporizhzhia. We have not yet spoken directly so far now I just share the information and you can read his updates for yourselves.

I understand there is (warranted) skepticism around individuals fundraising as volunteers. I would never have been able to raise any funds for Cards for Ukraine had I not earned credibility over time by talking about and documenting my volunteer work. The same goes for those helping in Ukraine. Transparency and taking the time to report on what you are doing and how is absolutely necessary. As this war drags on (and I think one thing everyone can agree on is no one sees a quick end in sight), I keep thinking more and more about the help needed IN Ukraine, therefore as I come across worthy projects, I will share them here.

Thank you so much for reading and for your continued support.