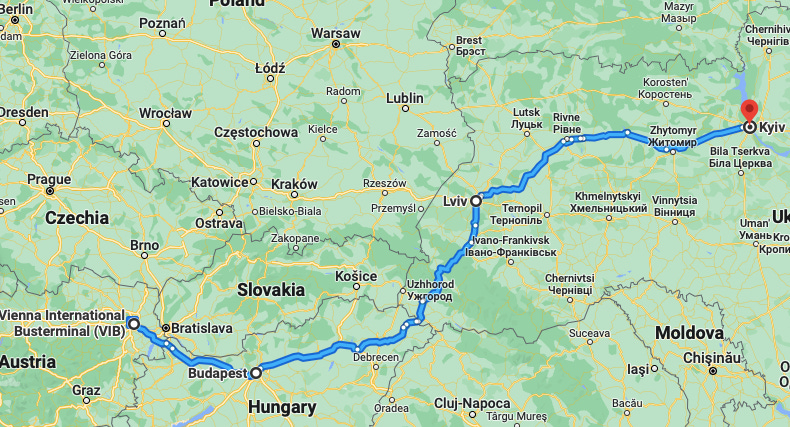

Vienna to Kyiv by bus

The first in a series of ten posts about my recent short trip to Kyiv.

The Vienna “international” bus station is a dingy parking lot next to a busy road and and overhead bridge. I realised the moment I arrived (an hour too early, airport habits) that I was not prepared, having not packed any snacks (airport habits), only one small bottle of water, and not fully understanding how I could make one last trip to the paid toilet (€0.50) with all my luggage. I had made the naive proposal to offer to take a few “small” packages to Ukraine with me, and naturally, several Ukrainians took me up on the offer. So I was left standing with far more luggage than one would normally take for a short trip. I found the bus, and cautiously passed one heavy suitcase full of other people’s deliveries to one of the two drivers. He grunted about which section was for Kyiv passengers, and it was at that moment I realised “direct” bus doesn’t exactly mean direct, if people are hopping on and off along the way. With one bag in tow, I managed to haul it over the entrance gate to the filthy WC. Five minutes before departure, Vasily, who helps me administer my Telegram group for Ukrainians in Austria, ran up to the bus, passing insulin & more needles to me. I asked him to talk to the driver, afraid that I might be told I had too much stuff. By this point my fellow passengers were making their goodbyes, and settling in for the long drive. They, unlike me, all looked like they had done this before.

The bus was not new but not ancient. The A/C worked. Wi-fi only worked in Ukraine. There is one toilet by the door and it was all of our job, we were told jovially in Ukrainian by one of the two drivers (both sturdy lads as one would say in English, who normally do the Germany routes, they explained) that it was our job not to plug up the toilet with “whatever ribbons and buttons you girls use” (it rhymes in Ukrainian) or we would all be screwed. I began to panic when I realised not every seat had a plug to charge a phone, but breathed a sigh of relief when I saw there was a plug by the window seat, and the young woman sitting next to me agreed to let me plug my phone in for a while. She was travelling alone and from her phone calls and our chats I could discern she has a job in Austria and is going home to visit her parents in Kyiv.

Across the aisle from me sat a mother and her daughter, the most amazing child. I couldn’t tell if she was seven or ten as she was small in stature but so mature and reading proper chapter books. Her mother was glued to her two phones (!) and she had come prepared with a power bank. The little girl was incredibly resourceful at self entertaining. No i-pad. No begging for snacks every 5 minutes. She had a fluffy green frog notebook with a lock and key (which she carefully tucked in the front pocket in a tiny plastic bag) and a pencil case of neatly organized colors. She calmly drew picture after tidy picture, a red-headed girl wearing an avocado t-shirt, a toadstool mushroom and a little bunny. When she bored of that, she read — chapter books, in Ukrainian. Mother and daughter spoke Surzhyk which is essentially a perfect mix of grammatically correct Russian with Ukrainian words thrown in about 50% of the time. At least that is what it sounded like to my ears. I listened, fascinated.

By now, I understand many common Ukrainian words. Everything to do with days of the week, time, months, common words distinctly different from Russian like buryak for beetroot or kordon for border. I listened, fascinated as this little girl copied her mother, weaving these two languages together, wondering if asked which one she would say her native tongue was. They were, as I understood, heading back to Ukraine for good. They had been in Tirol, and got off in Zhytomyr. During the second day of our trip, the little girl made friends with the boy seated behind her. They were about the same age. The three of them played Uno then together and even kept a complicated score, counting points, round after round, until the first who got to 150 won. I had never seen anything like that either. In the end, the boy told the girl (both M names, so sweet) he too was staying in Ukraine “forever” now, and they hugged to say goodbye when she and her mother got off first, and he continued onto Kyiv. The boy kept receiving video calls from his friends via his i-Pad, and saying a very adult-like voice “I can’t talk right now, I’m on the bus.”

55 people sharing a tight space for nearly a day and night requires everyone to behave considerately, and the Ukrainians did this, to perfection. It was quiet, no one yelled, no one ate stinky food (maximum someone would pull out slices of bread and make a few ham sandwiches on the flimsy tray in front of them). As we drove through Hungary towards Budapest, I watched the little girl’s mother make videos on her phone of the wind-power mills, and eavesdropped on a conversation about a family who fled Irpin on March 22. As the sun set over wheat fields, a woman recounted the story of how one family deciding to leave, the sister pregnant, and at 10am they fled their Irpin home. At 11am, a rocket hit it. They eventually returned to Irpin. A granny recalled the only thing worse than the holodomor is war itself.

There were conversations about all the money Ukrainians had invested in the EU, their contribution to the Polish economy. I sense, and this became a pattern, a general frustration amongst Ukrainians that they are perceived as a collective burden on the EU now rather than a contributing economic force. They know that Europe is “sick of us”. Around 9pm we pulled into Budapest, and I realised, naively, for the first time, that the bus would actually be making all the stops on our itinerary. We had 10 minutes to get off, for smokers to have a smoke (many preferred vapes), a quick run to a WC or to buy a snack. I didn’t see anything enticing, and decided I would wait until morning to eat (airplane habits).

As it grew darker, and we headed east towards the Hungarian-Ukrainian border at Zahony, I managed to get some sleep, thanks especially to one of those little foam neck travel pillows I stole from my almost-thirteen year old. At 3am we awoke to the surreal tune of Losing my Religion playing on the radio softly, and were told to get off the buss. Hungarian passport control. It was chilly and we lined up in our summer t-shirts and shorts, half-asleep, to have our passports stamped by grumpy Hungarian border control. Thankfully, I realised in retrospect, they didn’t go through our belongings.

We drove over a narrow bridge over the little river which forms the physical border, and then a Ukrainian soldier boarded our bus, rifle hanging across his chest, and told us each to open the photo page to our passports. We complied. He studied each carefully. Some time passed, a border guard came on board, and collected all our passports. More waiting, another soldier brought all the passports back, stamped with the date and time of our crossing. The entire crossing took “only” a few hours. By 5am we were watching the sunrise over the gas stations on the outskirts of Chop. A well-fed stray dog greeted us. We lined up to buy hot dogs and coffee. You had to use a QR code on your receipt to make the machine make your coffee. There was much yelling as some folks slowed down the process and others were nervous they would not have time to make their own coffees. The drivers filled up the bus with gas. We hovered outside for a few minutes. There was a palpable sense of relief to be back in Ukraine amongst the passengers. Two women explained to me the bus would now stop every few hours in towns as we drove through the west of Ukraine towards Kyiv, about another 800 km.

I was so tired from not really having slept much, but I also wanted to stay awake, as the scenery in western Ukraine, in the region where the Carpathian Mountains emerge and you have hilly private farms dotted with mushroom-shaped haystacks with pitchforks carefully placed next to them, is really different from the flat plains of Poland or Hungary. Those come later, as you head towards Lviv. The road itself is not a highway, but a single lane in each direction. There are massive potholes. It is bumpy. Sometimes, the bus stopped randomly along the side of the road, and a passenger would get off there, met by relatives with a car, or a package would be handed over. Sometimes the official bus stop was the parking lot of a 24 hour grocery store chain.

The western Ukrainian countryide reminded me in many parts of rural Serbia. Neat homes built with one’s own hands, high fences, small-scale private agriculture. You are hard-pressed to find any Ukrainian home that hasn’t planted its own vegetable garden and flowers. A car parked on the grass. Sometimes it is thirty years old. As long as it still works, it is used. Rural bus stops which I did not manage to get a photo of as I was sitting on the aisle, but imagine concrete lego blocks painted pastel pink with a blue and yellow pattern painted on top in the shape of the (full) map of Ukraine. Beautiful churches of various architectural styles in each town you pass. Next to each church is a cemetery, and in each cemetery you see large Ukrainian flags. Those mark the graves of soldiers who died in the war. Every village has a few. What you also see in the most western parts of Ukraine, and I only saw them there, are this flag hanging next to the Ukrainian flag. It is a controversial symbol which historically has been associated with nationalist movements. I was surprised to see it hanging on some official buildings (a school, and administrative building). But once you get to Lviv and beyond — I did not see the black and red flag (good explainer here) publicly displayed anymore.

We headed towards Lviv and it grew flatter and the trees disappeared. The kind of plains I remember from Poland and parts of Austria. The kind that make you think about 20th century history and past wars. Unfortunately, we did not get to see beautiful historic Lviv (which I have never seen!), but rather the completely crowded and chaotic Lviv bus station. The drivers managed to manoeuvre our bus into something resembling a parking spot, and we had 10 minutes to jump out. It was hot, and I didn’t have any local cash yet. Vasily had given me a Ukrainian bank card with about €25 on it, but the kiosks at the bus station were not all card-friendly. Although, to be fair, you can pay with a card for nearly anything in Ukraine, and by the end of the trip I was shamelessly wiping my card even for 1 Euro transactions (I had run out of cash). We all stocked up again on a little bit of junk food. The problem is by this point you really only want real food, and it isn’t readily available. You would rather go hungry, and think about the proper burger or soup you will eat in the evening. The Lviv bus station is also filled with ads for buses to desinations across Germany, Poland, Italy. An important reminder that long before the war started, there has been a huge flow of Ukrainians from the west of the country travelling to central Europe for work. Easy-to-access Polish work visas and other schemes made this possible, so even legal work was accessible. These earnings flowed back into the Ukrainian economy, and helped pay for many of the cars and homes and apartments and renovations we drove past.

My seat-mate, a pretty young woman of no more than thirty, asks the driver if she can continue to Kyiv. She bought a ticket only to Lviv, thinking she would want a break, but realises she would rather just push through. He agrees. They work it out between them. There is by this point a familial atmosphere on the bus, and especially between drivers and passengers. The older ladies refer to the drivers as “khloptsi” which is Ukrainian for guys or young men, but also carries a connotation of respect. It is a distinct word from the Russian term, and one of the easy indictors the person you are speaking with is Ukrainian when this word is used.

We head east, past fields and fields of corn and sunflower. The breadbasket to the world starts to take on a tangible meaning.

The single-lane road we are driving on also packed with 18-wheelers and other lorries, all carrying goods across the country. There are police often on the side of the road, handing out speeding tickets, managing fender benders. At one point we have to slow down (it is often a sudden hitting of the brakes by the driver which makes us all try not to fling forward into the seats in front of us), as an ancient open cart on wheels filled with water bottles, dozens and dozens of blue plastic water bottles, has lost one of its wheels and is now partially blocking the road. Four men in shorts and sliders mull around inspecting what to do. We merge into oncoming traffic to pass the accident. And on it goes.

Our route passes through mid-sized, nondescript cities like Rivne and Zhytomyr. I begin to see more closely the Soviet era apartment buildings that look like they might just collapse if the wind blew too strong, the ancient buses and vans still used for local public transportation, a pleasant local “lake” with a “beach” and next to it a faded yellow sign with red writing indicating the route to the nearest shelter. It becomes quickly very clear that no one is heading to shelters anymore.

In Rivne we are given 15 minutes at a local market at the bus stop, and there the everyday poverty hits me in the face. I have been working closely with Ukrainians of all different backgrounds for a year and a half now, but I have not seen where they come from. I see how ordinary people are scraping by, and it is quite shocking when you first arrive. I lined up for the paid toilet (6 UAH, about €0.15). I searched for something to eat, and bought a sandwich I was afraid might kill me (I have an irrational fear of mayo), but at that point I was more worried I might faint in the heat without eating anything. I snapped these four photos quickly, not wanting to draw attention, but realising I was looking at images the world doesn’t get to see often. Ordinary life in an ordinary town in a country currently at war where pensioners receive $80 per month as a pension and their utility bills can cost $50 or more. If you don't grow your own vegetables, somewhere, somehow, you will literally go hungry. I was also surprised to see so many Ukraine-themed chocolates and bags, and this continued everywhere I went. The country is not only militarized, obviously, as it is at war, and men in uniform of all ages are everywhere, but in full patriotic mode, too. You see “Ukraine” t-shirts of all designs being worn by ordinary people as they carry about their daily business. When air raid sirens ring, they often ring across the whole country. While I was there, rockets hit objects in Lviv and Lutsk. Both west of Kyiv.

We continued east towards Kyiv, and finally forests began to emerge, the familiar trees of the hilly Kyiv region landscape. Elderly men and women sat on the side of the road, just outside the woods, selling foraged wild mushrooms and homemade honey on little foldable plastic tables. Cars were pulling over on the side of the highway, and there was active trade, just like I had seen earlier in western Ukraine, as grannies with handkerchiefs on their heads tied at the back sold fruit from their own trees and tomatoes from their own gardens in front of their old country homes on the side of the Lviv-Kyiv road. And cars were stopping and buying. I suppose that is one of the ways one can supplement a pension that it isn’t enough to live on, especially if you don’t have kids to help you. On very rural roads, especially near villages, it is not uncommon to see bicycles being used on the side of the highway. Despite obvious dangers, if you don’t have a car and a local bus comes only infrequently, bike is the way to get to the larger town where shops and infrastructure are.

It is a hot, sunny afternoon and with all the stops we are told by one of the two drivers that we will likely only arrive in Kyiv by 6pm. We were scheduled to arrive at 3:40pm. Zhytomyr is dusty, gray, with wide Soviet-era boulevards and buildings, most of which look like its been decades since they saw better days. The mom and daughter sitting next to me start to get excited and pack up. They are getting off here. They talk about school, how they will have to choose which school the girl will attend from next month. Perhaps with so-and-so’s son, do you remember him? I start to think about how they made this decision. How did they decide it was “safe enough” to come home? I don’t want to ask personal questions, having just spend 24 hours listening in. But I wonder what will happen to this brilliant little girl, who now knows a bit of English and a bit of German and clearly is wise beyond her years. What will her future look like? They get off the bus and no one immediately meets them. Mother and daughter walk off towards the main road, pulling their suitcases. I wonder how long it has been since they were home. I wonder what the adjustment is like once you have experienced life in “Europe”. Do you see home through a different lens?

As we get closer to Kyiv, finally, my seat-mate calls a girlfriend, talks about all her plans: pedicure, a home-cooked meal from mom, maybe a trip to the seaside with her dad — he wants to go to Mykolaiv, she knows its dangerous, but she promised him, just three days, a birthday dinner celebration with wine and Georgian food in a downtown Kyiv restaurant. She explains it wasn’t for nothing she worked so hard in Luxembourg. I get the impression she has been in Europe for longer than the war. When we chat over our snacks in Rivne, she tells me her sandwich tastes “just like back when we were in school”, and I am overcome with that horrible melancholy when you speak a language well enough that people assume you are one of them, but you are not. And you did not go to those schools. And you did not know what the sandwiches tasted like back then. It is a constant feeling of not truly fitting in anywhere, and it gets harder to carry around the older you get. When you are young, it is a novelty. As you age, it just becomes more to explain.

Finally, the road widens into two and three lanes in each direction, and the giant apartment blocks and new office towers of Kyiv’s skyline emerge. The bus grows excited. The driver asks if anyone needs an extra stop. No. We go straight to the central bus station, which is directly next to Kyiv’s main train station. At this point I have a migraine from lack of coffee and Diet Coke. I start googling how long the pharmacies work for. I happily remember I am in post-Soviet capitalism and everything is open near 24h. I have plenty of time. I breathe a sigh of relief.

The bus station itself is total chaos. Rows and rows of buses and vans and taxis zipping in and out. It is hot, dirty, dusty, and mega busy. I wait for an elderly couple whose daughter and three grandkids are in Vienna. They are due to pick up a package from me. They are late and lost. I curse myself for having agreed. I try to buy a coffee but the Monkey Coffee kiosk only takes UAH or bank transfer. I can offer neither. My head feels like it will explode. Finally, the grandparents, aged 60-ish, arrive, both ever so pleasant, both ever so polite, and they give me some chocolates to say thank you. I order a Bolt, and the granddad walks me and my suitcases to the car. My driver has all the windows down, music blasting, and insists on lifting all my bags himself. I smile, happy to be back in the part of the world where men don’t let women break their nails nor their backs lifting shit.

In five minutes, we weave through the leafy green streets of central Kyiv, a fascinating mixture of old pre-war buildings, many of which look like they are slowly crumbling, Stalin-era blocks which remind me of the Moscow I once loved so much, and new shiny towers. A mix of everything. We pull up in front of my hotel — an American chain, half empty except for a mixture of diplomats, military-looking advisor type guys, NGO workers, and perhaps a few journalists. The Bolt costs me about €2. I leave a nice tip. I check in and am immediately instructed to download the air raid app and told it is strongly suggested we head to -2 floor in the garage when the sirens go off. My head is pounding so hard by now all I can think about is getting my hands on some ibuprofen.

I walk down the street about 20 meters to the nearest pharmacy which is open late 7 days a week. I ask for Nurofen, she tells me to take the Ukrainian brand. “Works faster. 400mg.”. I nod and pay with Vasily’s card. I speak Russian everywhere and am answered to in Ukrainian. It works, for the most part. The older the person, the less likely they are to be annoyed that I am not speaking Ukrainian. If a young person is really annoyed by Russian, I offer to switch to English. It’s the best I can do. I understand most Ukrainian pretty well by now, but I cannot speak it.

My impressions of Kyiv that first evening in the next post, part two of ten. Stay tuned…

What a treat! Thank you Tanja. this is marvelous.